Many people, who report having insomnia, seem to get far more sleep than they assume. A study published by MedUni Vienna's Department of Neurology (Outpatient Clinic for Sleep Disorders and Sleep-Related Disorders) is the first scientific analysis comparing PSG data to how much sleep a patient believes they have had.

By Jason Matthews

Insomnia can be a giant pain - Image Credit: amenic181 via Shutterstock / HDR tune by Universal-Sci

It is estimated that up to 60% of the world's population suffers from some form of sleep disorder and up to 30% from insomnia. It has been documented that there is often a discrepancy among patients about how much sleep they believe they get when compared to data obtained through sleep studies.

A research group led by Karin Trimmel and Stefan Seidel at MedUni carried out a retrospective study of polysomnograms (PSG) data collected from 303 patients who reported having sleep disorders between 2012 and 2016. A PSG measures the physical parameters associated with sleep. PSG's record data on breathing, muscular activity, and whether the subject is in light, REM, or deep sleep.

Trimmel and Seidel wanted to discover how often discrepancies between actual and perceived sleep occurred, how those discrepancies related to the type of sleep disorder, and what factors affected those discrepancies.

Out of the 303 participants, 51% were men and 49% women, 32% suffered from insomnia, 27% had sleep-related breathing disorders, 15% had sleep-related movement disorders, 14% suffered from hypersomnia/narcolepsy, and 12% from parasomnias. Trimmel and Seidel analyzed the subjects' PSG measurements and compared them to the patients' reported perception of how long it took them to fall asleep and how long they slept for.

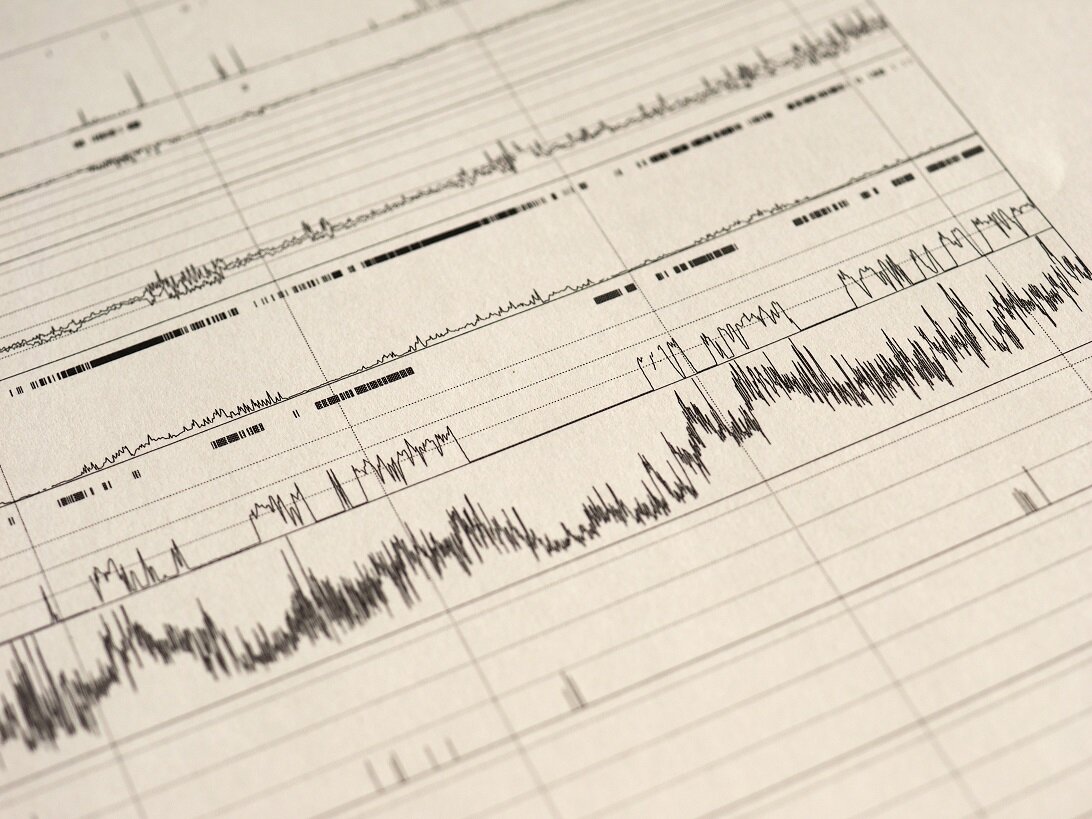

Polysomnography (PSG) is a extensive recording of biophysiological alterations that happen during sleep. They are often used in sleep studies like this - Image Credit: t50 via Shutterstock / HDR tune by Universal-Sci

All the disorders had noticeable discrepancies between actual and perceived sleep, which did not appear to be affected by age, gender, or background. With most of the less-common sleep disorders, the patients underestimated how long it took them to fall asleep and over-estimated how much sleep they had. However, those suffering from the more common insomnia sleep disorder more frequently over-estimated the time it took to fall asleep and under-estimated how much sleep they had.

This may suggest a reversal of the 'sleep placebo' effect may be occurring in people who report having insomnia. The study confirms the observations of other sleep studies that sleep misconception is ubiquitous in all sleep disorders but far more frequent in insomniacs. The cause of this phenomenon is likely underlying stress or psychiatric disorders, which may be increasing the number of microarousals during sleep. Cognitive-behavioral therapy may be the best form of treatment for insomniacs who under-estimate their quality of sleep. Karin Trimmel explains: "By incorporating this misperception into behavioral therapy, we can significantly improve treatment outcomes so that polysomnography is highly recommended for patients with treatment-resistant insomnia."

Further reading:

If you enjoy our selection of content consider subscribing to our newsletter (Universal-Sci Weekly)

FEATURED ARTICLES: