By Adrienne Macartney - University of Glasgow

Image Credit: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin (G. Neukum)

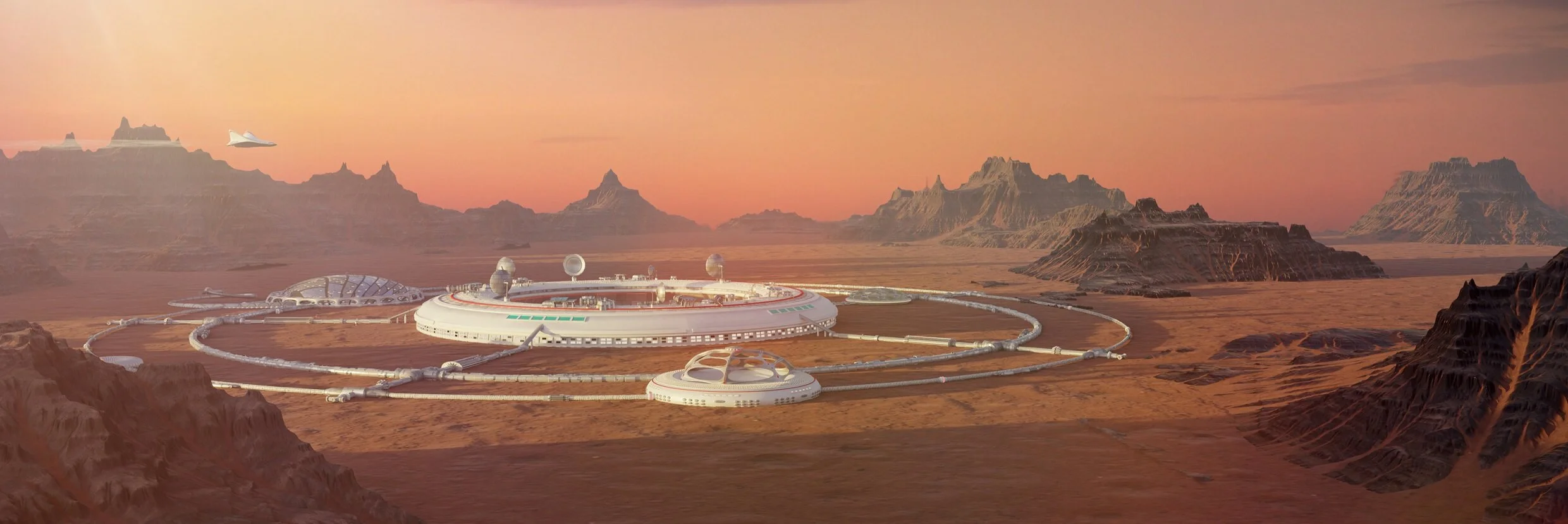

The surface of Mars is a cold desert. Scars in the landscape point to a history of flowing rivers, standing lakes and possibly even planetary oceans. Yet the current Martian atmosphere has a density that’s around 0.6% of Earth’s, making it far too thin to support liquid water – or life – on the barren surface.

At some point in the planet’s history, however, there must have been a thicker, denser atmosphere, probably dominated by carbon dioxide (CO2). And working out what happened to all that CO2 could help us deal with the increasing amount of the gas in our own atmosphere, which is pushing us towards dangerous climate change.

So where did the Martian atmosphere go? A large amount was lost to space, stripped away by the solar wind. Some has been stored as CO2 ice at the poles, where it remains today. But part of the atmosphere was transformed into carbonate minerals and preserved through the millennia. Using a combination of satellites and rovers, as well as evidence from meteorites that have been ejected from Mars and landed on Earth, we are beginning to understand how this process of mineral carbonation can change an entire planet’s atmosphere.

Humanity has actually become very good at capturing CO2 from the atmosphere through a wide variety of techniques. Once captured, the CO2 is usually compressed into a dense liquid. The problem comes in storing this liquid safely and stably, over millions of years. One exciting new development is called “mineral carbon sequestration”. This is the process of transforming CO2 gas into a stable mineral called carbonate.

Image Credit: RikoBest via Shutterstock / HDR tune by Universal-Sci

Turning CO2 into rock

How does CO2 gas become solid rock? If CO2 gas dissolves in water it produces a weak acid, called carbonic acid. When this acidic fluid comes into contact with rocks known as basalts and peridotites, which contain lots of the minerals olivine and pyroxene, they release charged particles of elements such as magnesium, iron and calcium into the fluid.

More chemical reactions between the rocks and carbonic fluid produce the solid, carbon-rich mineral carbonate, which fills cracks and pore spaces in the rocks. The carbon goes from being an atmospheric gas to a mineral deposit. During this process of alteration, the original rock minerals absorb huge amounts of water into their structure. This hydration causes the rocks to expand and crack, exposing fresh rocks that can also react with the water.

This process of mineral carbon sequestration happens naturally on Earth, particularly in ophiolites, pieces of oceanic crust that have been transported and pushed up onto continental plates. The natural reaction proceeds very slowly, over hundreds of thousands of years, and the carbon extracted from the atmosphere is an important sink for carbon ejected by volcanic eruptions.

Iceland is experimenting with carbon mineralisation - Image Credit: Johann Helgason via Shutterstock / HDR tune by Universal-Sci

But if we can artificially recreate this process, making it proceed at a faster rate, we can more safely store the CO2 we remove from the atmosphere. This kind of mineral carbon storage geoengineering is now being experimented with at a number of pilot projects including Iceland, Norway and the United States.

Researchers in these countries have discovered that the reaction happens much more quickly if the fluid temperature is raised to around 185°C. This heated fluid is injected down a borehole to the desired rock formation, where it stays hot because of the natural warmth below the Earth’s surface and because the reaction itself produces heat.

However, many questions need answering before the technique can be carried out on a large enough scale to be useful against global climate change. Ideally, we will need many hundreds of carbon injection sites, such as the CarbFix facility, dotted across Earth’s vast basalt wilderness regions. The challenges include fully understanding the chemical reactions between the rock and water, learning how to deploy these reactions fast enough, and more accurately estimating how quickly the CO2 will mineralise and the space it will take up.

Fighting climate change on another planet. - Image Credti: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

Mars’s loss, Earth’s gain

This is where we can learn from Mars. There is a near-endless variety of ways that unpicking the chemical evolution of one planet might better inform geoengineering actions on our own. For example, understanding the long-term fate of Martian carbonates and how they interact with the atmosphere and hydrosphere, will teach us how effective this form of carbon storage might be on Earth.

Analysing the carbonates found on Mars, the way reactions have taken place, and how carbon concentrations have changed across the planet, may help us to better understand the process of mineral carbon sequestration. New carbonate types might be discovered that provide clues about carbon-based minerals we think exist but haven’t yet been found on Earth.

The problem is there this is surprisingly little communication between Mars scientists and Earth climate change specialists. By combining the knowledge of these two groups, we may be able to control our global climate problems by using the planet’s rocky crust. Mars’ atmosphere loss may eventually become Earth’s climate change saviour.

Source: The Conversation