Researchers at the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden and Vita-Salute San Raffaele University in Milano have recently isolated different results in the two primary types of diagnostic testing done for Alzheimer’s Disease, previously thought to be similar. This discrepancy means that patients could possibly receive incorrect or delayed interventions based purely off of which test they receive, as well as influence the future of certain clinical trials for the disease.

Alzheimer’s diagnostics play an important role in determining treatment - Image Credit: Fresnel via Shutterstock / HDR tune by Universal-Sci

According to the Alzheimer’s Association in the United States, Alzheimer’s Disease is characterized by dementia that affects thinking, memory, and behavior. Eventually, symptoms grow severe enough as to interfere with the ability to do everyday tasks, as well as the possibility of premature death. Alzheimer’s is the most common form of dementia disease, touching roughly 50 million patients worldwide. One of the telltale indicators of Alzheimer’s disease is the accumulation of what are called plaques, which are amyloid proteins that form insoluble deposits in the brain. Currently, a large part of testing for Alzheimer’s Disease involves looking out for the presence of these plaques. This is where the differentiation in amyloid pathology screening methods comes into play.

Recommended further reading: What is the difference between Alzheimer's disease and dementia?

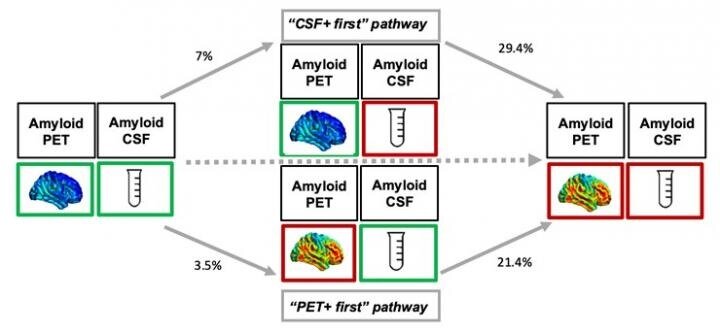

In addition to reviewing your medical history and symptoms, there are two primary testing methods for Alzheimer’s that are used to discover these plaques in the brain: a PET camera and an analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Research from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden and Vita-Salute San Raffaele University in Milano has now shown that in up to 20% of cases, often in early stages, these two testing methods can show different results in the same patient. Some patients show indicators of the disease in one test, but not in the other.

According to first author Arianna Sala, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Liège, Belgium and Technical University of Munich, Germany, “Today, CSF-analysis and PET are considered equivalent to determine the degree of amyloid accumulation, but the study indicates that the two methods should rather be seen as complementary to each other.” This could result in a large change to the entire Alzheimer’s diagnosis procedures worldwide— instead of using one test or another, either both would be used, or, if you are believed to have a genetic predisposition, one test might be recommended over another.

Schematic illustration of how brain imaging resp. cerebrospinal fluid measures the accumulation of amyloid protein. - Image Credit: Karolinska institutet researchers

But why would this difference in responsiveness to testing be occurring? For those patients who showed increased plaque levels in the CSF test over the PET test, they were more likely to have an increased genetic risk factor, as well as an overall faster accumulation of plaques in the brain. This indicates that the CSF test might be better at catching Alzheimer’s with those who are genetically predisposed to the condition than the PET scan alone could be.

The implications of this finding don’t stop at just how diagnosis procedures are utilized, however. Early diagnosis by using the correct test, or both tests, means earlier interventions, which are helpful in delaying onset of worse symptoms. Additionally, knowing that those with a genetic predisposition to Alzheimer’s respond more to the CFS test could also influence how new clinical trials of medication trying to reverse or slow plaques in the brain are conducted.

This study, "Longitudinal pathways of cerebrospinal fluid and positron emission tomography biomarkers of amyloid-β positivity", was funded by the Alzheimer's Foundation, the European Union Innovative Medicines Initiative AMYPAD, the Dementia Foundation, the Brain Foundation, the Swedish Research Council, the Foundation for Strategic Research (SSF), the Ake Wiberg Foundation, and Region Stockholm.

Sources and further reading:

FEATURED ARTICLES:

If you enjoy our selection of content please consider following Universal-Sci on social media