It has been the subject of movies, books, scientific discussion, and even music for longer than living memory. But has there ever been life on Mars? If so, where did it thrive? A new theory says it could have existed in vast underground lakes below the surface.

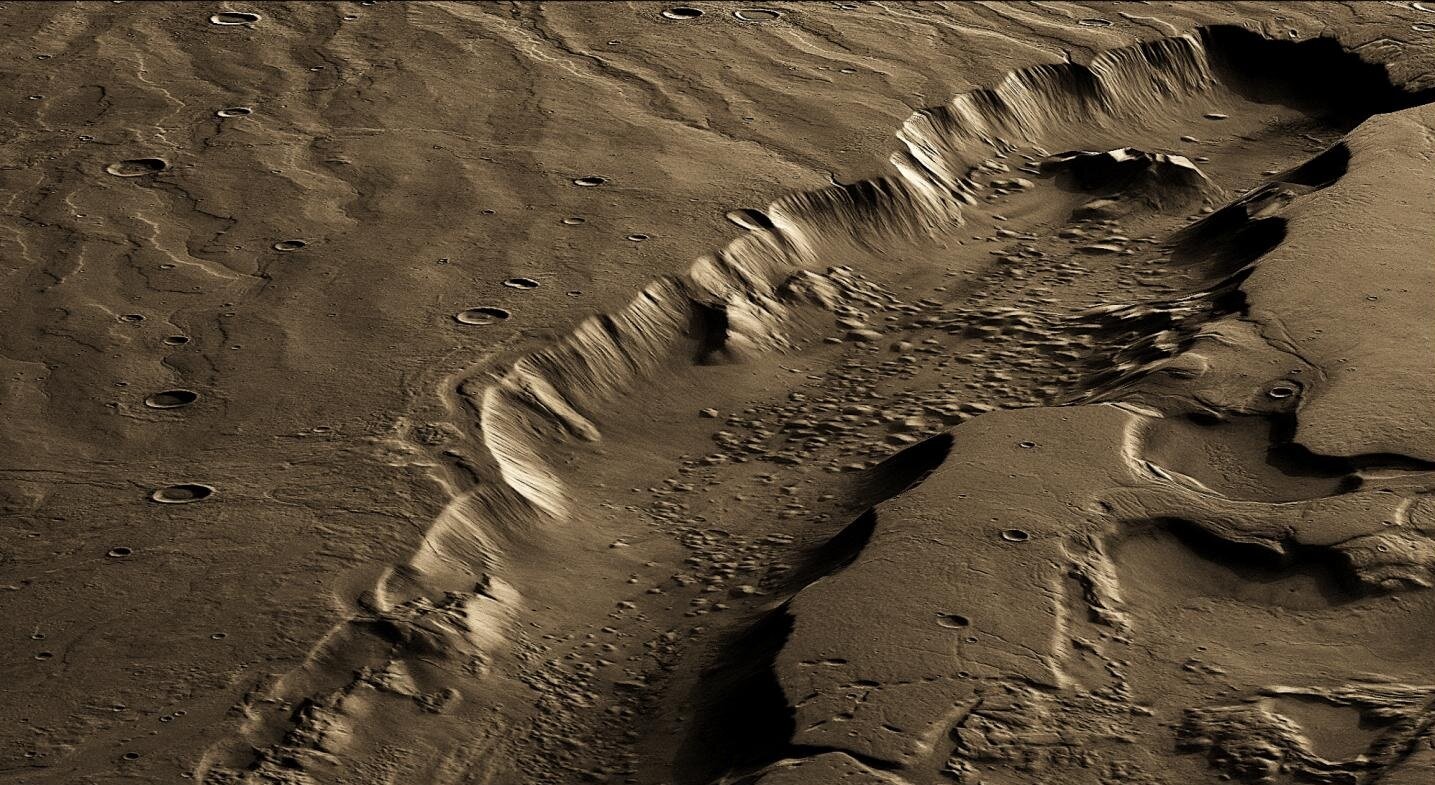

Dao Vallis, a large, channel on Mars cared by water - Image Credit: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO. 3D rendered and colored by Lujendra Ojha, HDR tune by Universal-Sci

The faint young Sun paradox

Travel back 4-billion years, Mars had an atmosphere, not unlike the early Earth's. Scientists have long pondered the possibility that life may have begun and developed along a similar path. But there is a problem. Around this period [named the Noachian era], the Sun was much dimmer and cooler than it is now. The Earth's thick atmosphere, geothermal heat, and closer proximity to the Sun allowed water to remain liquid and life to develop. But Mars is much further out in the solar system, meaning it should have been a frozen wasteland where no life could survive. However, evidence collected by Mars probes and landers contradicts this. There is geological evidence on Mars that indicates the existence of liquid water flowing freely during the Noachian era. This is known as the 'faint young Sun' paradox.

Hydrothermal habitats

Scientists have carried out computer simulations, factoring in greenhouse gases that could have been produced by Mars's many volcanoes. But none were able to convincingly account for enough warmth to reconcile the faint young Sun paradox.

Lujendra Ojha, an assistant professor at Rutgers University and the lead author of a paper that attempts to answer this inter-planetary riddle explains that he and his co-authors proposed that the faint young sun paradox may be adjusted, at least in part, if Mars had high geothermal heat in its past.

Mars - Image Credit: WR Studios via Shutterstock

Geothermal heat is produced by the radioactive decay of elements like uranium found in the core of rocky planets like Earth, Mercury, and Venus. It is reasonable to entertain the possibility that Mars may be the same. If Mars produced enough geothermal heat during the Noachian era, it would explain how liquid water could have existed, albeit mostly sub-surface. As the Martian atmosphere was slowly lost to space and the surface temperature and pressure fell, liquid water would have only remained stable deep below the surface. Any life that did evolve would have had to follow the liquid water to ever greater depths.

According to Ojha, it would have been possible for life to be supported by warmth resulting from hydrothermal activity in addition to rock-water reactions. Consequently, the subsurface might be the longest-lived inhabitable environment on Mars!

Ojha and his team think that Mars InSight spacecraft will allow researchers to further evaluate the role that geothermal warmth played in regard to the habitability of Mars during the Noachian era. For now though, if you are interested in learning more about the Mars habitability study, be sure to check out the paper published in ‘Science Advances’, listed below.

Further reading:

FEATURED ARTICLES: