As we get older, many of us experience age-related cognitive decline to varying degrees. An example would be not being able to connect the face of someone you just met to their name. This can be very upsetting to those involved. It is not known to scientists why the above-mentioned 'malfunction' happens.

However, researchers at the Maryland School of Medicine have found some interesting evidence on why our associative memory capacity degrades as we get older. And on a hopeful note, they also uncovered an opening for potential treatments.

In this article, we will have a look at their findings.

Image Credit: fizkes via Shutterstock / HDR tune by Universal-Sci

In short, the Maryland team has discovered an unexplored mechanism occurring in neurons that makes the memory of social interactions fade as we get older.

Through a paper published in the peer-reviewed science journal: Aging Cell, the researchers report that their study revealed a precise target in the brain that can be utilized to design treatments that could deter or even reverse memory loss resulting from typical aging.

Memory issues brought on by aging differ from those brought on by illnesses such as dementia or Alzheimer's disease. There are currently no treatments that can stop or reverse cognitive decline brought on by normal aging.

Associative memories

Dr. Michy Kelly, lead researcher, illustrated typical age-related cognitive decline with an example. She referred to an older person that went to a party. After the party, they would probably be able to recognize the faces or the names of other people that attended the party. The issue, however, centers around connecting the correct names to the right faces. In other words, there is a problem with associations.

These so-called social associative memories, which link various bits of information within a personal interaction, require a particular enzyme (PDE11A) in a brain region responsible for memories that involve life events.

PDE11A turns out to be an extremely interesting enzyme, as previous research done in part by Dr. Michy Kelly involving the same enzyme showed that PDE11A even influences who our friends are. (The study demonstrated that mice that had genetically comparable versions of this enzyme were more likely to connect with each other compared to those with a different type of PDE11A.

With this new study, the researchers strived to discern PDE11A's role in social associative memory in the brains of older people. And if altering this enzyme can be employed to avoid memory issues like these.

The study

The team studied the social interactions of mice by looking at whether they would be willing to try new food based on their recollections of encountering that food on the breath of other mice.

The underlying idea behind this is based on the fact that mice don't like to try new food sources in an attempt to avoid illness. A new type of food can be dangerous for them.

When they sense food on the breath of other mice, they make a connection between the scent of the other mouse's pheromones and the odor of the new food. If they remember this, it can serve as a signal that the food is safe to eat in future encounters.

Findings

Interestingly the researchers discovered that, even though elderly mice could distinguish between food and social scents on their own, they were not able to recall the relationship between the two, which is similar to cognitive impairment in older humans.

On top of that, the team also uncovered that levels of the aforementioned enzyme become higher as mice (and people, for that matter) get older. This effect is strongest in the brain area that plays an essential role in things such as spatial memory and merging information from short-term memory to long-term memory; the hippocampus.

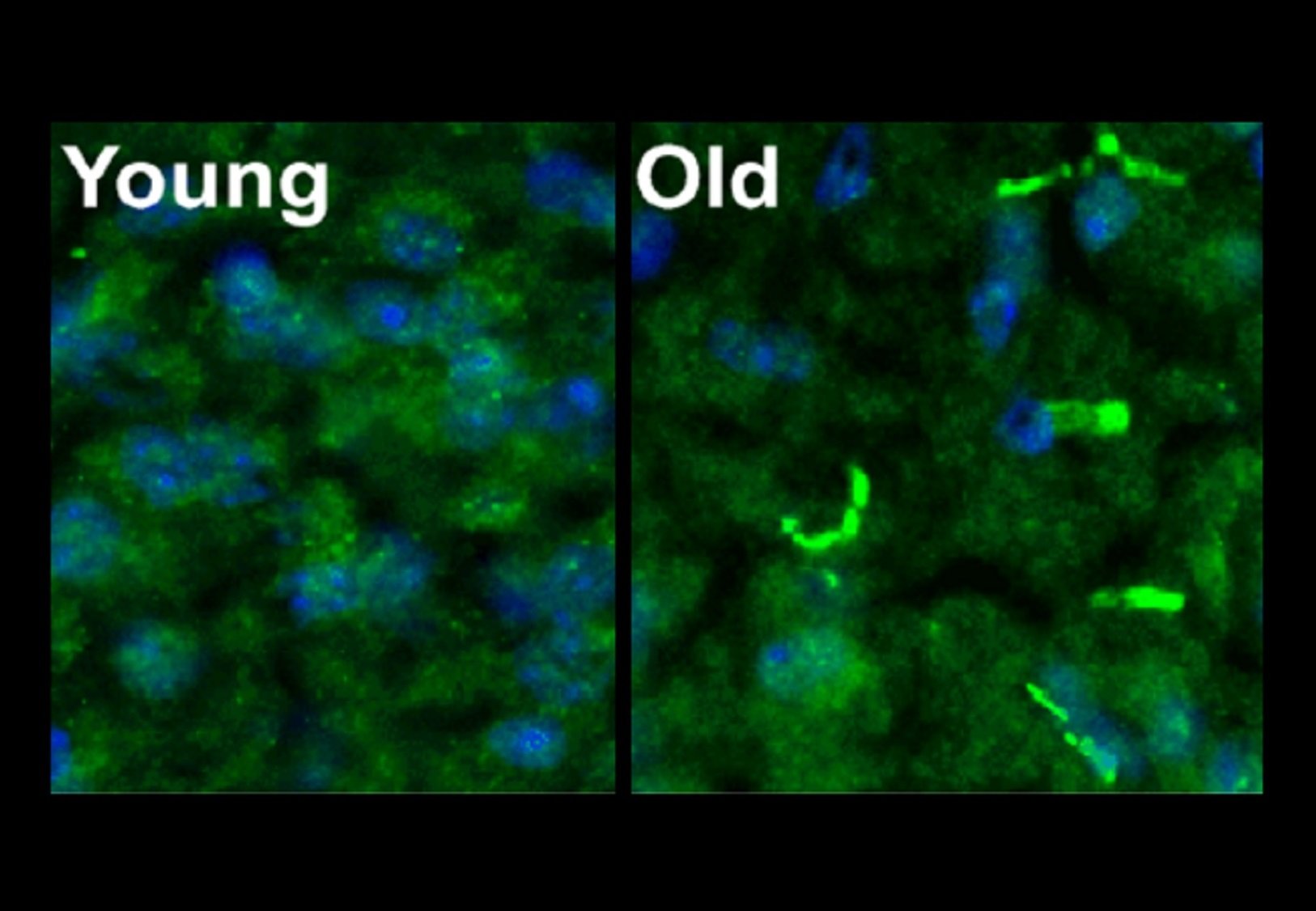

In contrast to where it would typically be found in young mice, this additional PDE11A in the hippocampus preferentially accrued as tiny filaments in compartments of neurons.

Seen here in green is the PDE11A enzyme. On the left in the brain of a young mouse, on the right in the brain of an older mouse. (Image Credit: University of Maryland School of Medicine edited for size by Universal-Sci)

Restoring associative memory

The scientists pondered whether the excess PDE11A in these filaments was the cause of the older mice's loss of their social associative memory and their refusal to consume the safe food they could smell on other mice's breath.

In order to find out, they stopped the accumulation of the enzyme by deleting the PDE11A gene. Without it, the elderly mice stopped losing their social associative memories. They actually ate the new foods they previously smelled on the breath of other mice.

Doing the exact opposite also turned out to be possible; when scientists added the PDE11A gene back to the older mice, they lost their associative memory once more. And, consequently, stopped eating the unknown food.

All in all, these new findings could mean a lot towards future treatments for age-related memory loss. Of course, as is often the case, more follow-up research is needed to build on this growing body of knowledge.

Sources and further reading:

A genetic basis for friendship? (Molecular Psychiatry)

If you enjoy our selection of content consider subscribing to our newsletter (Universal-Sci Weekly)

FEATURED ARTICLES: