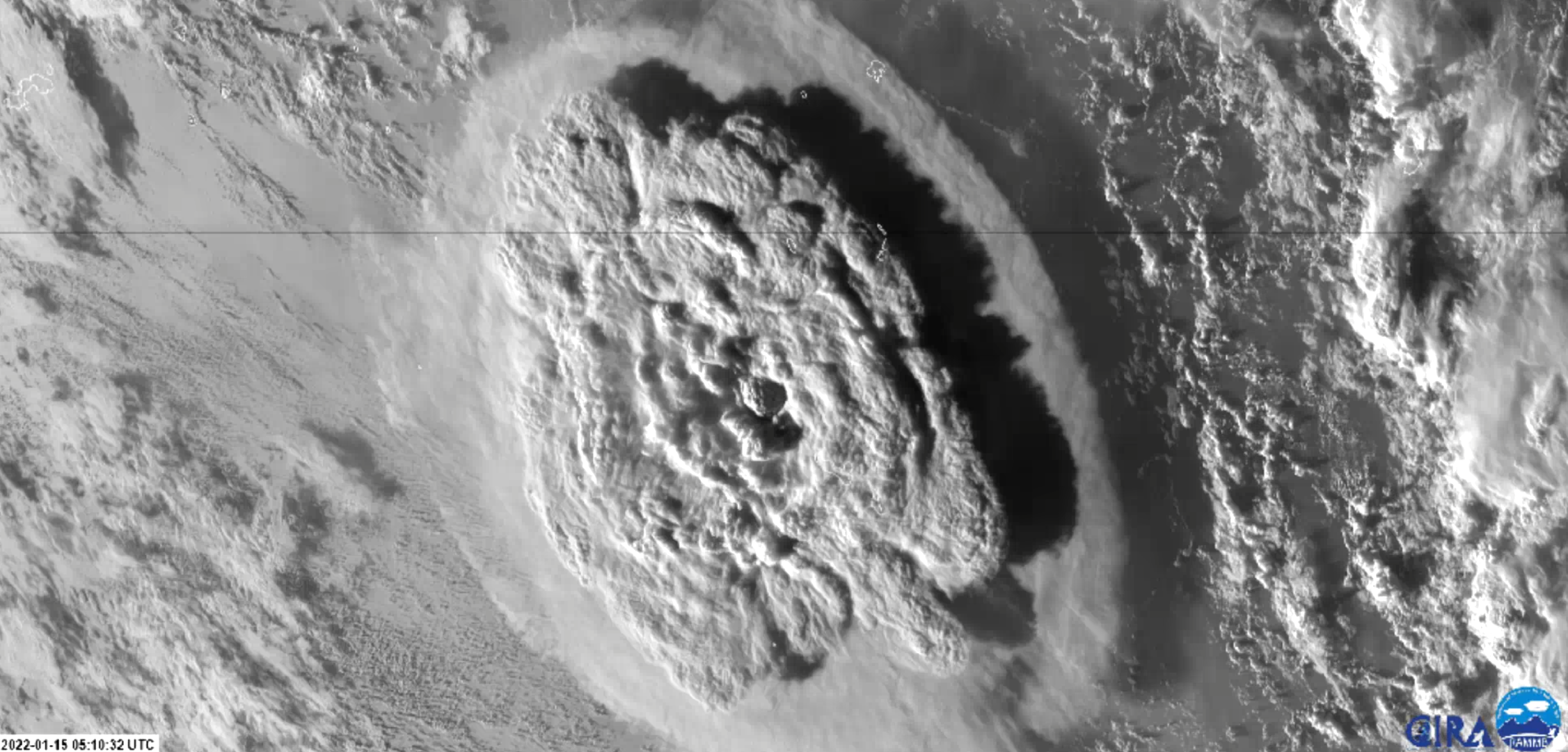

A powerful volcanic eruption took place below the surface of the island group of Tonga in the Pacific Ocean on January 15. Hot magma came into contact with cold seawater, contributing to an explosive eruption of volcanic gases and ash particles. The explosion generated strong pressure waves in the atmosphere, which were detected around the entire planet.

Large volcanoes have had an impact on the global climate in the past. Many people asked whether this eruption will have a similar long-term effect.

The Tonga volcanic eruption as observed from space - (Credit: NOAA/CIRA/RAMBB)

Rising temperatures in the stratosphere but falling surface temperatures

The large amounts of ash and sulfur particles that end up in the stratosphere due to the volcanic eruption (above about 11 miles/18 kilometers altitude) absorb sunlight, heating the stratosphere.

Meanwhile, less sunlight reaches the ground, which causes surface temperatures to fall. The ash and sulfur particles are expected to spread with the wind all over the Earth in the upcoming months.

The last major eruption to significantly affect the climate was the Pinatubo volcanic eruption on the Philipines in 1991. As a result of the enormous amount of sulfur dioxide emitted, our planet cooled by 0.2 degrees Celcius in the following years.

That effect is equal to a fifth of the temperature rise of 1.1 degrees since 1900, caused by humans. Nonetheless, it only lasted for a relatively short period of time. After 2 to 3 years, most sulfur particles had descended from the stratosphere, and most of the ash had vanished from the air after a few months.

Mt. Pinatubo, a giant active stratovolcano, as seen from the air - (Credit: Alyona Naive Angel via Shutterstock / HDR tune by Universal-Sci)

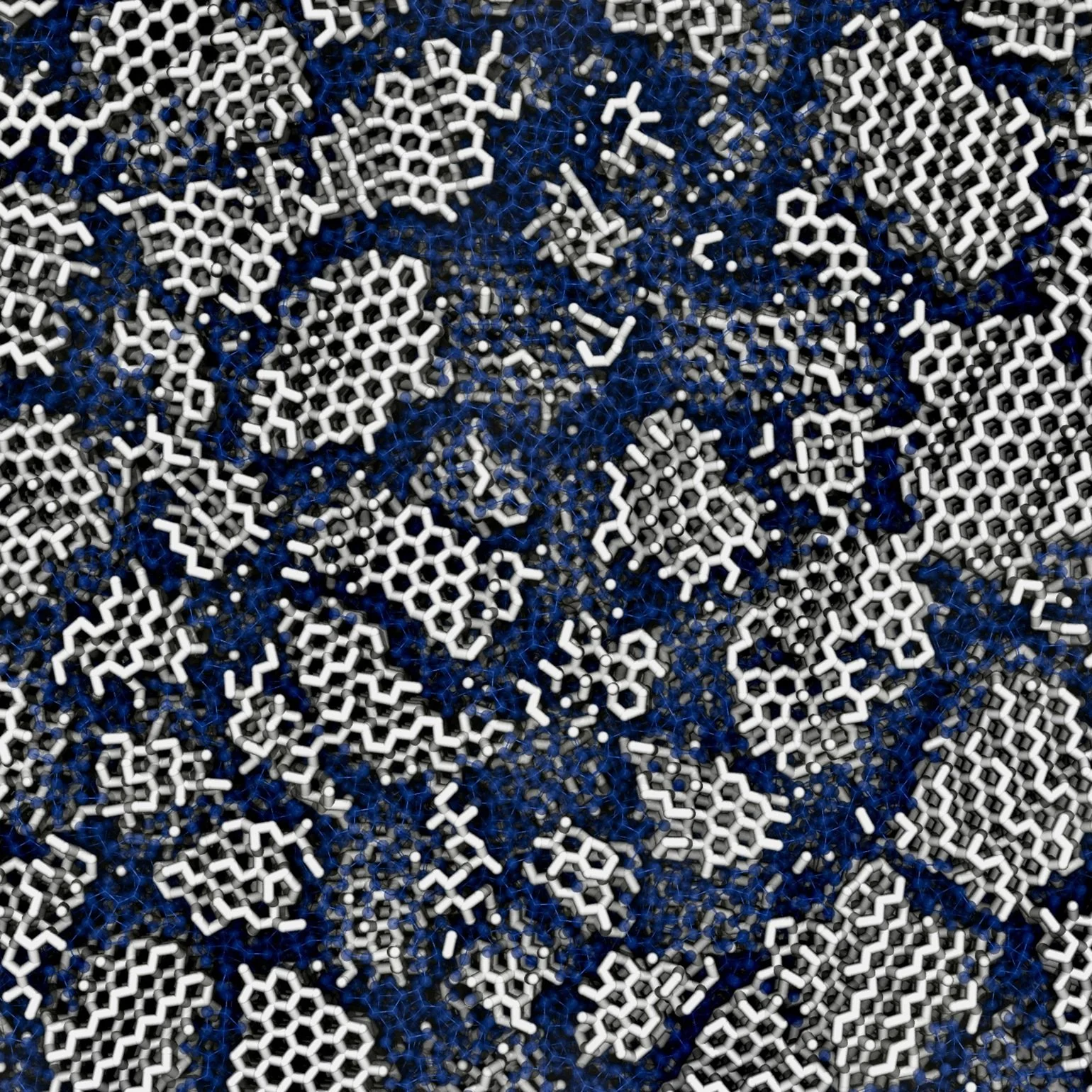

What about other particles?

In addition to ash and sulfur dioxide, volcanoes also emit CO2 and water vapor. The extra water vapor will quickly return to the surface in the form of rain, but it takes years before the extra CO2 disappears from the atmosphere.

However, even with large eruptions akin to the aforementioned Pinatubo eruption, CO2 emissions were small (0.05 Gt) compared to emissions from human activities (36 Gt per year).

All volcanoes together emit an average of 0.26 Gt per year, while it takes humans only three days to emit the same amount. The contribution to the total amount of CO2 in our atmosphere, and thus to global warming, is relatively small for the Tonga eruption.

Big volcanic eruptions strengthen westerly winds

Powerful volcanic eruptions in the tropical zone in which the plume reaches the stratosphere can have an effect on the climate that lasts for several years.

Polluted air rises further in the tropical stratosphere, from which it then flows relatively slowly towards the poles. This allows the tiniest sulfur particles to remain in the stratosphere for several years, affecting climate for an extended time.

This phenomenon can cause long-term climate variations in other regions. Sulfur particles absorb most of the sunlight in the tropical stratosphere, which is the region where most of the solar radiation enters.

As a result, the stratospheric temperature difference, as well as the differences in air pressure between the tropics and the poles, will increase, resulting in stronger westerly winds (westerlies) in both the stratosphere and the troposphere. These stronger winds, in their turn, lead to more evaporation from the North Atlantic Ocean, cooling the climate.

Image Credit: OSweetNature via Shutterstock

Will the Tonga volcano have any lasting effects on our climate?

This relationship between volcanic eruptions in the tropics and long-term climate variations in other regions applies not only to the past 150 years, for which relatively many measurements are available but also to the past 1000 years. This is apparent from indirect measurements, such as the thickness of tree rings as a measure of temperature.

Luckily, early estimates indicate that the amount of sulfur dioxide from the Tonga eruption is 50 times smaller than the Pinatubo volcanic eruption; scientists, therefore, do not expect significant, lasting climate effects this time around.

Sources and further reading:

National Environmental Satellite Data and Information Service (NOAA)

Evidence for a volcanic underpinning of the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation (Nature Climate and Atmospheric Science)

Multidecadal climate oscillations during the past millennium driven by volcanic forcing (Science)

If you enjoy our selection of content, consider subscribing to our newsletter - (Universal-Sci Weekly)

FEATURED ARTICLES: